THE PASSION OF THE MUMMY

PREFACE

A key to a happy life may be a stable childhood. As children, we think of many things as permanent. To the best of our knowledge, those things have always been, and always will be. For the fortunate among us, parents are strong and nurturing, friends loyal, families intact, health good, and our fundamental needs met. Part of growing up is realizing, and reluctantly accepting, that nothing lasts forever.

My first years were indeed stable. In addition to the basics, Dwight Eisenhower would be the only President that I knew until I was 10, and the New York Yankees dynasty lasted until I was 14. About that time, the years and the injuries (and the hard living, as I would later learn) took their toll on my idol, Mickey Mantle, but through my earliest years, he rarely let me down.

Perhaps the truest symbols of permanence were the awe-inspiring buildings that I sometimes visited with my family or on school trips. In my youth, I thought that all of them stood on Manhattan: Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, the Empire State Building, the American Museum of Natural History, the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Even Manhattan’s main post office on 34th Street seemed more a monument for all ages than a place to mail a letter.

The fall of such edifices indeed signaled the transience of any human endeavor. The first to vanish during my life was The Scripps Museum of Manhattan.

* * *

The Scripps was to Egyptian relics what the Barnes Foundation near Philadelphia was to turn-of-the-20th Century painting: labors-of-love for independent millionaires who had no liking for the museum establishment. The Scripps, a magnificent marble and glass fortress, housed Sebastian Scripps’ massive private collection of antiquities. Handsomely endowed by Scripps, who died in 1924, the museum funded expeditions to Egypt, and continuously added to its impressive holdings. By the time that I was 9 years old, and made a fourth-grade class trip there, The Scripps had one of the finest collections in the world, clearly surpassed only by the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities in Cairo (popularly known as the Cairo Museum), and certainly the equal of anything in the Americas.

The Scripps was to Egyptian relics what the Barnes Foundation near Philadelphia was to turn-of-the-20th Century painting: labors-of-love for independent millionaires who had no liking for the museum establishment. The Scripps, a magnificent marble and glass fortress, housed Sebastian Scripps’ massive private collection of antiquities. Handsomely endowed by Scripps, who died in 1924, the museum funded expeditions to Egypt, and continuously added to its impressive holdings. By the time that I was 9 years old, and made a fourth-grade class trip there, The Scripps had one of the finest collections in the world, clearly surpassed only by the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities in Cairo (popularly known as the Cairo Museum), and certainly the equal of anything in the Americas.

“Old Scripps,” wrote a New York newspaper in his obituary, “would have bankrupted himself to outdo The Met, whose curators he despised.” The Met is the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, then and now the premiere art museum in Manhattan, with a Victorian neo-classical exterior as impressive as The Scripps.

The Scripps closed forever within a year of my first and only visit, and the same demolition contractors who would tear down the once-majestic Pennsylvania Station in 1963 did the same to The Scripps.

Did financial mismanagement bring down The Scripps, or was its demise due to betrayal from within? The root causes of The Scripps’ downfall are still debated, but its board of directors and top curators, like The Scripps collection itself, were handsomely divided among a handful of major museums. Chief among them was Scripps’ arch-rival in all things Egyptian, The Met.

Even during its heyday, The Scripps was not an easy place to visit. Appointments were required, and anyone not associated with an institution respected by Scripps and later by his board might not enter at all. No one from The Met need apply. It was never a place for a family outing or a casual stroll-through during lunch hour. The museum had no gift shop, and no cafeteria. Still, its collection was magnificently displayed, perhaps for no one other than the ghost of Scripps himself.

* * *

When I started fourth grade, Miss Hedden, my grammar-school art teacher, announced with great enthusiasm that she had arranged a class trip for a day at The Scripps. Sixty-four of us would go—16 from each of the four grammar schools in North Arlington, New Jersey (all named for presidents: Jefferson, Roosevelt, Washington, and my school, Wilson), spread over Grades 3 through 6. Miss Hedden spent one day a week at each school (what she did on the fifth day, I never learned), and would choose the lucky students based on criteria never revealed. I later suspected that we were chosen based on who best behaved themselves. Certainly, then as now, my talents and interests in any form of art were slight, but I never gave my teachers any trouble (unless included is one substitute teacher, whom I now am pretty sure was a paranoid manic-depressive).

The name “Scripps” meant nothing to any of us, but we all felt lucky because the trip gave us a day away from school. Perhaps we shared a smidgen of pride that, according to Miss Hedden, The Scripps had never hosted a school class trip before (and would not again). We were the first and only. Miss Hedden had studied under a professor who later became a curator at The Scripps. Also, Miss Hedden was the only one of my grammar school teachers whom I might call “young and pretty.” I would not see a male teacher until I was 11, and all the women teachers of my youth were much older than my mother. So, my guess is that Miss Hedden’s charms had much to do with her wrangling a trip to The Scripps for her students.

On a bright, crisp, cool November morning, 64 eight-to-eleven-year-olds poured through the huge bronze doors of The Scripps Museum. Perhaps we—boys, girls plus Miss Hedden and our seven chaperones—appreciated the details of the collection in various degrees, but we all were overwhelmed by its appearance. The exterior of the museum looked like a kitschy Greco-Roman temple that we might see in the movies: Columns with ornate crowns, marble facades, huge painted murals. The interior columns of the cavernous atrium were covered in brightly painted hieroglyphs. The museum was as much a testament to Sebastian Scripps’ ego as to the grandeur of ancient Egypt.

Whether love of Egypt or love of self drove Scripps to build his museum, I cared not. I was enthralled, and so were my classmates. We could not imagine that, within a few years, the collection would be dispersed, and the building itself demolished.

* * *

The 64 students were comprised of 37 girls and 27 boys. We had to pair up for the “buddy system” to keep an eye on each other. No boy-girl pair was allowed, nor desired by the adolescent students. Mixing the grades or the different schools was avoided as much as practical. The only siblings on the trip were twin girls and three pairs of brothers. The twins were paired, but the brothers kept far apart, as they might be the most likely to fight. After some awkward back and forth, the buddies were established, and I wound up on one of two “threesomes.” That was fine with me, since—unless I could be with my best friends (none of whom were on the trip)—I wanted to be alone, and ditching two “buddies” would be easier than ditching one.

The 64 students were comprised of 37 girls and 27 boys. We had to pair up for the “buddy system” to keep an eye on each other. No boy-girl pair was allowed, nor desired by the adolescent students. Mixing the grades or the different schools was avoided as much as practical. The only siblings on the trip were twin girls and three pairs of brothers. The twins were paired, but the brothers kept far apart, as they might be the most likely to fight. After some awkward back and forth, the buddies were established, and I wound up on one of two “threesomes.” That was fine with me, since—unless I could be with my best friends (none of whom were on the trip)—I wanted to be alone, and ditching two “buddies” would be easier than ditching one.

Bright and sunny when we left New Jersey, but, as we neared The Scripps, the sky quickly grew dark, and a lightning bolt struck quite near us. We had just learned how to tell the distance of lightning from us. As soon as the bright flash streaked through the bus, some of my classmates and I began to count “One thousand, two thousand” and so on. Before we reached “two thousand” came an overpowering clap of thunder. “Wow,” said Mike, one of my fellow fourth-graders, “that was less than 1,000 feet away!”

“Nothing to worry about,” said a chaperone. “It probably hit something in the river. Be careful when you get off the bus.”

We normally would have lined up next to the bus before going in the museum. But with rain threatening (though none came, but wind and more lightning did), we were quickly ushered, single file, into The Scripps’ huge atrium. A group of museum personnel stood outside to greet us. All of them wore what I assumed were Egyptian costumes.

“Wow, The Scripps is going all out,” whispered Miss Hedden to one of the chaperones. “They really want today to go well. I hope it does.”

A man whom I presumed to be a museum director, dressed as a pharaoh, greeted us, said a few words that I could not quite hear, and motioned us toward the entrance.

Standing at the door was a tall man almost fully covered in a linen robe. Only his face and hands were visible. One of my more adventurous classmates asked, “Are you a sheik?”

“No, young man, I am garbed as a Bedouin chief. Bedouins are a nomadic people who roam the deserts of northern Africa and Arabia. They have alternately allied and warred with Egypt from time immemorial.”

The garbed, oddly-accented man spoke with an authority that commanded good behavior. Few of us could take our eyes off him—no mothers present to say “don’t stare!”—and he never took his eyes off us. The boys and the girls congregated together as we entered. The Bedouin appeared only to count the girls, but I thought he stared at each boy.

He looked into my face, and I still cannot forget the chill that went through me. Perhaps still, more than 60 years later, the most penetrating eyes that I have ever seen. I had seen such looks before, but never as intense. I assumed the Bedouin was silently telling us to behave. I knew that day that he would be getting no trouble from me.

* * *

Four women, about the same age as Miss Hedden, awaited us in the atrium. All were trim, tall, dark, and clothed in Egyptian garb of similar design but of different colors. The Scripps, though intended for serious scholars, was not without dramatic flair. Four Cleopatras would be our guides, whom we remembered as Cleo Red, Cleo Blue, Cleo Green and Cleo Gold. Miss Hedden divided us into four groups by grade, each with a Cleopatra and two chaperones.

The Scripps had four halls: The Hall of Weapons & War, The Hall of Amulets & Jewelry, The Hall of Carvings & Stone, and The Hall of the Dead. That last hall held the mummies. After the introductory talk on the history of the museum, and the usual admonitions (no running, no touching the exhibits, stay with your group, no photography, no smoking—for the chaperones, I presumed—no chewing gum, and no food or drink), the tours began. Each group would visit the halls in a different order. My Blue Group of fourth graders would see the Hall of the Dead last.

I wish that I could say that I remembered more of what I saw that day. The Hall of Weapons & War had what we called “cool stuff,” but even there I soon hit overload. Simply too much to take in. I would not have grasped a lot of Cleo Blue’s lecture even if I had paid close attention. After a while, everything just fused together. The Scripps tried hard to give us a good day at the museum, but just overwhelmed us. What kept me going was the ominous allure of the Hall of the Dead.

I was tired and bored by the time my Blue Group reached that hall. I looked closely at the mummies, but, as I walked with my group, I felt sick. Everything ached. I was nauseous and sweaty. I had all the symptoms that I now associate with the flu, but it was not the flu. I did not know what it was. I stumbled toward a display case with a mummy in its coffin. I started to lean on it, when a hand gripped my shoulder and pulled me back.

A deep, heavy voice asked, “You are unwell, young man, or perhaps a bit fatigued?” It was the Bedouin, again looking deeply into me.

“I don’t know,” I said. “I feel a little funny.”

He was no longer in Bedouin garb. Now, he wore a dark pin-stripe suit and tie, and a turban. Before that moment, I had seen men wearing turbans only in the movies—movies like Gunga Din and Wee Willie Winkie—but never in the flesh.

The turbaned man placed his hand under my arm, and started leading me away. He raised his other hand, and got the attention of Cleo Blue and the chaperones. Our guide only nodded, but one of the chaperones approached us. He was stopped by a gesture from the turbaned man. Another wave of his hand must have signified that he would take care of the problem. Cleo Blue moved between the chaperone and me, and whispered “Fear not, he will look after the boy.” She also had an odd accent.

The turbaned man led me to a door at the side of the hall, unlocked it with a huge key, and walked me through it. He locked the door behind us, and flipped a light switch.

* * *

I was expecting a bathroom or at least a place to sit down. In the room were only two display cases. The lighting was within the cases. As my eyes adjusted, I saw eerie shadows reflected off the walls. These, like so many walls in the museum, were brightly painted with scenes and hieroglyphs.

I was expecting a bathroom or at least a place to sit down. In the room were only two display cases. The lighting was within the cases. As my eyes adjusted, I saw eerie shadows reflected off the walls. These, like so many walls in the museum, were brightly painted with scenes and hieroglyphs.

One mummy case was like the cases in the hall: glass surrounding a painted coffin, and a mummy lying in it. The mummy was particularly well preserved, and looked more like a carved figure of a beautiful woman than a dead body thousands of years old. No wrappings were on it. She looked as if a sorcerer had waved a magic wand over her while she slept and turned her to stone.

I read the plaque on the case:

PRINCESS ANANKA

THIRD DAUGHTER OF KING AMENOPHIS

The turbaned man asked “Do you know the name?” I shook my head no. “Is she real,” I asked. “Very” was the only reply.

I was feeling much better. The pain and the nausea were gone. In fact, I was feeling energetic. I turned to leave the room, but the turbaned man instead pushed me towards the second case. Unlike the others in the hall—indeed, unlike most mummy displays that I have seen since—its mummy stood upright. The case stood at the foot of the Ananka’s coffin, with only about three feet between them.

I read the plaque at its base:

KHARIS

PRINCE OF THE ROYAL HOUSE OF KING AMENOPHIS

I read that softly aloud, saying the name as “Car-iss,” accent on the first syllable.

The turbaned man corrected me. “That is the American pronunciation. Please say it as ‘Ca-reese.’” Accent on the second syllable.

“Imagine,” said my host, slowing shaking his head, “going through eternity with people mispronouncing your name.” I might have countered that, with my long Italian surname—accents on the second and fourth syllables—such might be my fate, but I was of no mind to contradict my host.

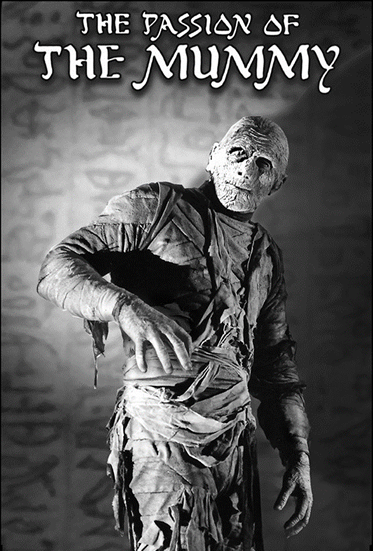

Kharis, however his name was said, was also in an exceptional state of preservation, though not as fine as Ananka, who might, it seemed, awaken at any moment. Kharis was wrapped head-to-toe. The wrappings across his face had so fused with the flesh below that his facial features could be discerned. Kharis’ most remarkable feature was his girth. All the mummies in the hall looked emaciated. For the unwrapped mummies, as many Scripps mummies were, barely enough flesh remained to cover the bones.

Not so Kharis. In life he must have stood over six feet, and in death looked like he weighed about 250 pounds. “He’s awful big for a mummy, isn’t he?”

“Yes, but he is at his biggest now. His size varies with the moon. Full moon tonight, you know.”

I looked at the turbaned man, and wondered if he were joking. He was not, though I would later learn that he did possess a dry sense of wit.

“Why is he standing, and not like the other mummies?”

“He’s better behaved when he can gaze at his princess. In your studies at school, have you read The Scarlet Letter?” I shook my head no.

“Please read it, perhaps for your next book report.” The turbaned man drew out the words “book report” in a mocking tone.

“Two sad lovers who could be together only in death.” The turbaned man exhaled slowly and deeply, and seemed very sad. “Their love was forbidden, but unbreakable. Only in death could they lie side-by-side in their graves. When Kharis and Ananka were first brought here—oh, let me see—some years ago now, their cases were laid side-by-side. That caused problems.”

I stared at the turbaned man, again to see if he was joking. I had no sense that he was. He turned that terrible gaze upon me. At that moment, from the corner of my eye, I thought that Kharis had turned to look at me. Of course, he had not. He was looking directly at Ananka.

“Kharis is much happier like this, gazing forever at his beloved.”

The turbaned man took me by the arm—rather too roughly, I thought—and positioned me at the foot of Ananka’s case, facing Kharis.

“Ah, you are just tall enough to break that gaze. Please look into his eyes. Tell me what you see.”

I looked directly into Kharis’ face. I felt rage, his rage that I dared come between him and Ananka. I turned to look at the princess, but the turbaned man—again too roughly—grasped my shoulders and returned me to facing Kharis.

“Now, look deeply into his eyes. Deeper. Tell me all that you see.”

* * *

I have no idea if I said anything after that. I had the strange sensation of falling. Falling and falling through a dark haze where I could make out only blurry images. How long I fell, I do not know. The haze finally lifted, and I was looking at Ananka. Not at her mummy but at her sleeping form. She was the loveliest woman that I had ever seen, but she was not sleeping. Her dead body lay before me. I felt an overwhelming sense of hopelessness and loss.

In my own life, at age nine, I had yet to know true grief. No one in my family, no one that I knew personally, would die before I was in my teens. There at The Scripps—but actually someplace else—I stood before Ananka’s body, crippled by emotions I could not understand. “Memories” came to me of holding Ananka in my arms and passionately embracing her. At age nine, I knew almost nothing about sex, but I think the “memories” included physical intimacies which I could not yet describe or understand.

A hand touched my shoulder. Not the firm hand of the turbaned man, but a gentle patting. I turned and saw an old man. He spoke strange words that I did not know, but I understood him. “You must be strong, my boy.” The old man turned me from Ananka and led me away. “There is no more that can be done. We must go and let the priests do their work.”

We walked a long corridor which might have been one of The Scripps’ grand halls. Tall stone columns with painted hieroglyphs, marble floors, painted and bas-relief murals on the walls. At the end of the corridor was a large pool of water. I saw my reflection in it.

I was no longer a boy, but a large man. The face was not my face. It had what I would later call “rugged good looks.” Strong features, dark hair, and a brow filled with sadness. I studied the face. I tried to smile, but the reflected face did not. I was sure that I was looking at the face of Kharis in life.

I—Kharis—sat on the side of the pool and wept.

* * *

How long I was in Kharis’ netherworld, I do not know. The next thing that I remember, I was boarding the school bus for the ride back to North Arlington. My legs buckled a bit as I climbed the steps and walked to my seat. Had I been asleep? Was my trip with Kharis only a dream? I did not know.

I took my seat at the window, and saw Miss Hedden outside the bus talking with some of the tour guides and with the turbaned man. Their conversation was light-hearted, and all were laughing. I sensed that the turbaned man was holding court and entertaining the ladies. He noticed me looking at him, walked toward the bus and tapped on the glass. School bus windows could only be opened a few inches. I slid back the pane as far as I could.

“I hope that you enjoyed your visit, young man, and I hope to see you again soon—very soon.”

I meant to ask Miss Hedden his name, but never did.

* * *

The aftermath of all class trips was an essay the next day on the experience. I remembered almost nothing of the day other than my time with Kharis and Ananka. So, I wrote of it as best as I could. Basically, I said that I stared into the face of a mummy, and was carried to his world. Had I been in 3rd grade (Mrs. Burke), 5th grade (Mrs. Keenan) or 6th grade (Mrs. Ruggles), the consequences of submitting such an essay might have been severe. But Mrs. Fanelli was a saint, and only wrote across the top:

A- I wasn’t expecting a daydream.

“Daydream,” I thought. Maybe that’s all it was. Though disturbing, the memories soon faded, and took their place among the few dreams in my life that I remember.

My schoolmates and I were almost The Scripps Museum’s last visitors. Shortly after that day in November 1959, the sorry state of the museum’s finances made the news. The endowment was all but gone, massive sums were unaccounted for, and bills had long gone unpaid. I would not have noticed such stories on the evening news, but, thanks to my day at The Scripps, my interest piqued at any mention of it. A Scripps-funded expedition in Egypt, which had just begun a new season of digging, had to be abandoned. The museum closed its doors forever.

Soon the grand collection was dispersed, and developers acquired the land. In 1960 the building was razed. As I watched the story on the news, I wondered about the fate of the grand murals and columns. Surely, they were not demolished. Or were they? And what became of the mummies, especially Kharis and Ananka.

The last mention of The Scripps on the evening news—which I saw only because it preceded Popeye the Sailor, which I never missed—came from a news-commentator:

Sebastian Scripps collected treasures thousands of years old to adorn a monument to himself that he intended to last a few thousand more. It lasted 36.