“Brent Marassas,” I told the pharmacist and slowly spelled my last name.

M-A-R-A-S-S-A-S.

I often picked up my father’s prescriptions. He and I had the same name, and I could sign whatever I had to and show proof of identity. When Papa was too ill, I signed any checks that arrived for him.

This time, the pharmacist surprised me. “Date of Birth?”

I paused and gave my father’s.

The pharmacist, “DePalma” by his nameplate, never looked up. Or rather, never looked down, for in our old neighborhood drug store, he stood on a platform about a foot above his customers. He was a short, squat man, and, even on his platform, his eye-level was only a few inches above mine.

As DePalma measured out the pills, he asked “Is that name Italian or Greek?”

I had been asked that many times and gave my usual answer. “I’m not sure.”

“You should find out.” He looked directly at me. The origin of my name was a sore point with me, as Papa never cared to discuss it.

I paid for the bottle of green pills, and as I waited for the receipt, read the label. The name meant nothing to me. Probably painkillers, I thought. Doctors rarely cured you but could relieve the suffering.

* * *

The time was a bit past noon. My Thursday had already been a long day. Marty, an old Army buddy of my father, had called me late Wednesday night. Whenever the phone rang after 9 pm, a chill ran through me. Was this the call that I knew must someday come? Not quite, not yet, but such a call could not be far off. Marty told me that Papa had taken a turn for the worse, and that he wanted to see me. Marty—widower and the last living member of his immediate family—was no stranger to tending to ill friends and relatives. He had the presence of mind to ask me to pick up a refill prescription on the way.

“He can’t be too bad if he’s getting more pills,” I muttered as I drove. Wishful thinking, I pondered.

From Bensalem, Pennsylvania to North Arlington, New Jersey is an 80-mile drive, most of it on the dreaded I-95. I first stopped at my office, tended to a few things that simply could not wait for my return, and told my boss my situation. He was alright with it. He had heard the same from me before. Papa had lingered at death’s door for the past few months, in and out of hospitals. No more hospitals, he insisted. Papa wanted to die in his own bed.

He had never summoned me before and seemed rather indifferent when I visited. I feared that now he felt his end was near.

As I got within range of the New York radio stations, I listened to the news on 1010 WINS. Not much going on. A follow-up story on the Ash Wednesday wildfires in Australia of three weeks before. A dry spell, a hot day and high winds combined to spread the blaze. Dozens dead, hundreds of houses destroyed, thousands of people evacuated. The only news was that Pope John Paul II was completing his Caribbean tour by visiting Port-au-Prince, Haiti.

* * *

Marty Piletti had served with Papa in the Pacific. Both were sergeants when the war ended. Marty was built like a bull. As a boy, I most often saw him in his butcher shop, wearing a blood-stained apron. I was a little scared of him then. As I grew, I saw that his imposing presence belied a sweet and compassionate nature.

That morning, he looked more tired than me and might have been up all night. In his exhaustion, he looked somewhat like Papa. I was never sure of my relationship to Marty. Any inquiries into the family were abruptly brushed aside when I was a boy, and strictly forbidden when I grew older. I had stopped asking many years ago. My mother passed when I was very young, and I never had the chance to learn anything from her. In terms of genealogy, I had been raised in a house of closed-mouth men.

That morning, he looked more tired than me and might have been up all night. In his exhaustion, he looked somewhat like Papa. I was never sure of my relationship to Marty. Any inquiries into the family were abruptly brushed aside when I was a boy, and strictly forbidden when I grew older. I had stopped asking many years ago. My mother passed when I was very young, and I never had the chance to learn anything from her. In terms of genealogy, I had been raised in a house of closed-mouth men.

“Your father rallied this morning,” Marty told me. “He’s got a lot of pep. It’s all I can do to keep him from getting out of bed. I’m going home to get some sleep. You stay with him.”

Neither Marty nor I took Papa’s resurgence as particularly good news. The dying often have a last burst of energy before their ends—a last hurrah of the old self held in reserve to set things right before they leave this world. Is that why he wanted to see me?

“You know,” said Marty, “you’re a lot like your father. You talk the same, act the same, think the same. The same impatience. He’ll live on in you long after he’s gone.”

I thought that an odd comment and only nodded. I walked up the stairs to Papa’s bedroom. As I neared, I sensed the unmistakable scent of a sickness—medicines, food on a tray, pajamas that needed to be changed, and the undefinable odor of an ebbing life. When the soul leaves this world, does it leave behind an ethereal aroma?

* * *

The first thing that I noticed in Papa’s bedroom was his rosary. He had always kept the beads in the top drawer of his dresser. They had been there since I could remember. Now, he held them wrapped around the palm of his left hand. On the end table sat his Bible, which also had always resided in the dresser, next to the rosary. The book was old and showed signs of wear, though I had never seen Papa read it.

Papa had indeed rallied. He looked younger than when I had seen him a week before. I leaned down to hug him. He returned the embrace. He was very warm. Not feverish, but again that feeling of a life soon to end. Is the heat only the friction of the body’s battle to hold onto its soul?

As I sat down, Papa held my right hand in his left, only the rosary between our palms. He pointed the remote control at the television and turned it off. That television had been my last gift to Papa a few months before. It was as much a gift to Marty, who would no longer be called to change channels or volume when Papa could not get out of bed.

“I was watching I Died A Thousand Times. Ever see that?”

“Yeah. Remake of High Sierra with Jack Palance in the Humphrey Bogart role. I’ll watch the rest of it with you if you want.”

“No. The first half is better than the end. Lon Chaney just had his big scene as the dying crime boss. After that, it is not as good as the Bogart movie.”

Papa’s eyes looked deeply into mine.

“That scene is kind of like us now—the young guy sitting across from the dying old guy.”

“Don’t talk like that.”

“Why not? It’s true. I feel pretty good now, but how long will that last? No time left for diplomacy, kid. There’s something you need to do for me. I hope you can finish it before I go.”

“Anything. What is it?”

“Anything? Don’t be so anxious. You might think differently in a few minutes.”

Papa picked up his Bible and held it in his lap.

“I’ve been thinking about this a lot. Remember that project you had to do in the third grade, when you had to do your family tree? I refused to tell you anything.”

“Yeah, I made up some names and dates, and some stories. You were no help.”

Papa coughed, then laughed. “Sorry about that. But now there’s some things that I want to know, and maybe you should know, too.”

“Why now?”

“Some things I need to know before I go. Things I avoided before.”

“What? Why?”

I wondered if Papa heard me. He leaned his head back on his pillow and stared at the ceiling. So, did I. Nothing much to see there except a water stain older than I could remember. Papa seemed a bit older to me now.

“I always felt that part of me was missing. That there was something out there that was part of me.”

“What do you mean?”

Papa’s eyes left the ceiling and focused on me.

“How’s your World War I history?”

“Not very good.” A few dates and names of battles and men flashed through my mind.

“World War II history better?”

“Yeah, of course.” A large part of my growing up was watching war movies and documentaries.

“Then you know that when World War II ended, a bunch of German rocket scientists surrendered to the Americans rather than let the Russians get them?”

I nodded.

“Well, the same thing happened after World War I, except it is not in the history books. A bunch of scientists headed west to the Americans. The Americans didn’t know what to do with them. They got to America, alright, but no one was interested in what they were peddling.”

“They were making rockets and bombs? Gas bombs?”

Papa levelled his hardest stare on me, the one that I had seen often when I misbehaved as a child.

“No. They were making a special kind of soldier. Soldiers who were almost indestructible. Men who would not feel pain. Men who would never get tired. Who would know no fear, and never question orders.”

Papa drew in a deep breath.

“Men who have no mind or will of their own.”

“Sounds something like zombies?” I laughed. Papa was deadly serious.

“Call them what you will. Anyway, thirteen scientists—well, a kind of scientists, maybe—sent a messenger to an American delegate in Paris after the armistice, peddling their wares. They were all East Europeans. Germans, Austrians, Hungarians. They all fought with the Central Powers. Except they didn’t fight; they worked in their labs.

“Whoever the messenger met with didn’t know what to make of him and kicked him out. He might have done better going to the French. The French had experience with that kind of soldier. But the hatred among the Europeans ran deep. The Americans were seen as saviors of a sort.”

“How does this relate to us?”

“I’ll get to that. Those thirteen guys wanted to get to the Americas. Something there that they wanted.”

Papa took a sip from the glass of water on his end table. He coughed a few times and took a deep breath before speaking again.

“So, the Americans turned them down. A Captain Holland, the Canadian attaché with Pershing, had lived in the Caribbean. He knew about zombies. He talks to the Americans; he talks to the British; and somehow, they get across the Atlantic. Some to America, some to Canada. No one in the government and no university showed any interest in them. They spread out. Most wound up going south. The Gulf Coast, and the Caribbean. Three of them went to Idaho.”

“Idaho! Not exactly zombie land.”

“The United States was picky then about letting in dimwits. So, the plan was that an idiot brother would go to Canada, and he would get in America from there. Two of the scientists went with him and got him into Idaho.”

“Your father was the idiot brother?”

“Don’t joke about it. I remember Toby well. That’s almost all I remember of my time in Idaho. I was a kid living with my Uncle Richard. How he was my uncle—if he was a blood relation—I don’t know. Problems developed there. I don’t exactly know what. The police came, and I wound up going from home to home. One after another until I was 16. Then I ran away.”

Papa wiped his eyes. He often rubbed them, but was he now wiping a tear?

“Foster homes?”

“Not exactly. Those were not good years, but I was lucky. I didn’t get stuck with any of the psychos that a lot of foster kids dealt with. The homes were with the other scientists. I am pretty sure of that, now. When those guys weren’t at each other’s throats, they took care of their own.

“But you guessed right. One of the so-called scientists was my father. At least, I think so”

Papa pointed to a stack of large envelopes on a shelf across the room from his bed. I fetched them and handed them to him. Most were an inch or so thick. The older ones had faded with age. The others looked quite new and were much thicker. Papa picked up one of them.

“These are from a private investigator that I hired last year. His office is in the city. He mainly handles cheating husbands and small-time fraud, but he did a good job finding what could be found. I told him as much as I could remember about my past, and he took it from there. I want you to pick up where he left off. I want you to see him in New York before you get started. Then I want you to visit some places and find out what you can.”

“I doubt there are many World War I scientists still with us.”

“Yeah. None of the normal ones.” Papa gave me another long stare. We both remained silent for a minute or so.

“So, you want me to pick up with where this…”

I looked in the papers and saw a business card.

“…where this Harold R. Angel left off.”

“More or less. I want to know which of these guys, if any, is my father. Your grandfather.”

“So, all this Voodoo stuff is going on in Idaho?”

“Only a little in Idaho. Twin Falls, Idaho to be exact. Like I said, mainly the Gulf Coast and the Caribbean. One wound up in upstate New York, one in Nevada. But I haven’t said a word about Voodoo. You shouldn’t either until you know more. You’ll probably never know enough about it. Unless you’re raised in it, you may never understand it.”

“Were you raised in it?”

Papa shot me a harsh look that soon softened. He rubbed the rosary beads with his thumb and forefinger.

“Be careful. Those men came over as scientists, but some soon got into what can only be called witchcraft. That’s not really Voodoo, though. That’s Voodoo’s evil cousin, sorcery.”

I wasn’t buying all that Papa told me, and I wasn’t crazy about an enormous project being dumped in my lap. How would I ever finish what Papa was asking in time for me to tell him. And I didn’t know anything about zombies and Voodoo. Papa had had many years to investigate the family history himself. He could not face whatever the truth was, and now he wanted me to.

“And what about your mother? My grandmother?”

Papa wiped his eyes again, and no mistaking the tears this time.

“I never knew her, you know.” He coughed again. “We have that in common.”

“You’ll see that in Angel’s file. About the only thing those scientists—mad doctors, witch doctors, whatever—had in common was an obsession with their work. They made their slaves—zombies, automatons, whatever—and then made more. My mother—your grandmother—might be one of them. Some of these guys experimented on their wives. Or maybe the wives’ curiosity got the better of them, and they got too close to what their husbands were up to. You’ll see some of that in Angel’s files.”

Papa lifted his head off his pillow. An unwiped tear rolled down his cheek.

“Weird stuff, huh? You and I may be the result of ‘zombie-sex.’”

“Zombie-rape?” I had trouble taking Papa’s story seriously.

Papa shook his head.

“Maybe. Well, with your extensive knowledge of World War II,” Papa said sarcastically, “you can guess how some kids felt when they learned that their fathers were war criminals. Or how the Hitler Youth felt after the war. The ones that survived that is. That’s how I have felt for the past 40 years or so. But now I want to know, and I haven’t much time. I waited too long. Go find my daddy, kid. Warts and all. I want to know.”

As a little boy, I called Papa “Daddy.” He looked weary now. All the talking, with the strain of what he talked about, wore him down.

“You’ve got everything you need to get started. Unload that crummy job of yours and work on this. I’ll be gone soon, and after that you won’t have to worry about money for a quite a while. There’ll be some traveling in this. I’ll cover it. Don’t worry about costs. I have been saving my whole life, and I guess this is why. Now, go find my daddy.”

I only nodded, and Papa smiled back, then grimaced and rolled on his side.

“I’m tired. I need a nap. You look like you could use some rest, too. You need to be fresh before you dig into this.”

“First, one more thing. What was it that these scientists—our daddies—wanted in America?”

“They were looking for something that may only be found in the New World. Something that would help their work.”

“Like what?”

“Like what?”

“A plant or an animal from which could be extracted something with an odd effect on humans.”

“Zombie powder?” Again, I almost laughed.

“Call it what you will. A powder that destroys free will and makes its victims receptive to another’s will. Maybe another powder that increases a man’s willpower so that he can rule over others.”

“Hard to believe.”

“Yes, isn’t it?”

“And you believe that such a powder exists?”

“It has always existed. In some form at least, it has been known all over the world and through the ages. It is the stuff of legend. You will be learning about that, I suppose. In its primitive forms, it gives the appearance of death. With a little tweaking by sorcerers or scientists, it lets the so-called dead rise, but with no will of their own.”

“So, this stuff has been around forever, but nobody knows about it?”

Papa took a deep breath, exactly as he used to when I disappointed him.

“How’s your Shakespeare?”

“Not as good as yours.”

“You got that right. Bring me that book.” Papa pointed to shelf at the far end of his room. Old books lined the shelf. I picked up The Complete Stories & Poems of Edgar Allan Poe and The Complete Works of William Shakespeare. Both books had been there since I could remember. If Papa read them, he did so in private, but I knew that he was well-versed in Shakespeare.

“One of these?”

“Either will do. But bring Shakespeare.”

He took the thick volume, flipped through it, and then turned the pages one-by-one until he found the passage he was looking for.

“Here. Romeo & Juliet, Act IV, Scene I. Juliet is being forced to abandon Romeo and marry Paris. Friar Laurence hands her a drug that will give her the appearance of death. Here, read what he tells her.”

I took the book and started to read.

“Read it aloud. I could use a good reading of Shakespeare before I take my nap.” Sarcasm again.

A good reading was beyond me at the moment, but I did my best. Papa rolled the rosary beads between his fingers.

Take thou this vial, being then in bed,

And this distillèd liquor drink thou off,

When presently through all thy veins shall run

A cold and drowsy humor, for no pulse

Shall keep his native progress, but surcease.

No warmth, no breath shall testify thou livest.

The roses in thy lips and cheeks shall fade

To paly ashes, thy eyes’ windows fall

Like death when he shuts up the day of life.

Each part, deprived of supple government,

Shall, stiff and stark and cold, appear like death.

My reading did not impress Papa.

“You see, even in Shakespeare’s time—and long before—they knew of drugs that gave the appearance of death. Variants of that drug go well beyond just a death-like state. The dead rise and serve their masters. That’s what those scientists were after. So were sorcerers, witches, and shamans through the ages.

“There’s a binder over there.” Papa pointed to the same shelf. I returned Shakespeare to its place and took the binder.

“Read that before you get into Angel’s files and meet with him. It will give you some background that Angel does not go into.”

Papa looked drowsy. I took his left hand in mine, but he was already asleep.

Papa still had his command of history and Shakespeare, but was everything he told me only his fantasy? Was it an old man’s grasp at a personal history that he could never know?

* * *

While Papa napped, I went to my old room with the binder and large envelopes of papers. The room was pretty much as it had always been. Framed photos and magazine covers of my sports heroes hung on the walls. The same plaid spread covered my bed, just as it had when I was a boy. The hardwood floor showed the wear of when I did my morning push-ups and sit-ups.

At my peak, I would do 50 push-ups and 200 sit-ups before school. I got down on the floor and did 15 push-ups before I rolled over on my back, panting. I blamed my lack of sleep, but inwardly accepted that I was not in the shape I used to be.

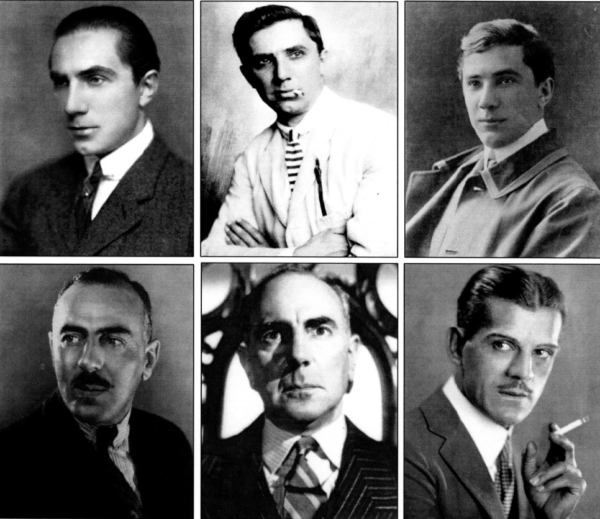

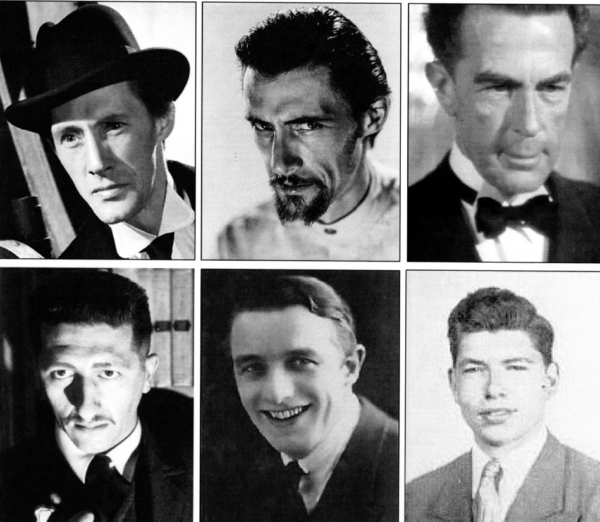

I lie on my old bed and thumbed through the photos that Harry Angel collected. Thirteen men, and if Papa was right, one of them was my grandfather. They were the east European scientists who had come to America immediately after what they would have known as “The Great War.”

I thought back to my third-grade class when I was eight years old. For our family tree projects, some of my friends brought in old photographs of their families. One kid had an entire album. I remember how I marveled that photos could be so old and different than the

“family photos” that I had ever seen. I was jealous that day and did what I could to make myself invisible.

Wow, I thought, if only I had the photos now in my lap back then. I could have said, “one of these guys is my grandfather, but I don’t know which.” We could have had a big discussion about who was who. And when I told my friends that these candidate grandfathers were scientists making zombies for the Central Powers, I would have been the star of the day. Instead, I spent most of that day embarrassed and envious—if only Papa’s curiosity about his roots had been piqued 25 years ago instead of now.

* * *

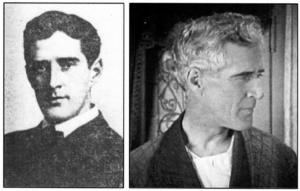

Harry Angel was nothing if not organized. One envelope for each suspect, and the first page of each had a summary of what Angel learned, and a photo stapled to it. The photos were of varying quality and age. Some were taken in Europe, some in America, and sometimes years after arriving in America. Some were studio shots, some copied from passport or ID photos, some clippings, and one seemed ripped from a high school yearbook. I would later learn that, when Angel was hunting for something, he was not too particular how he got it or what he had to destroy to get it.

Some of the 13 took different names on entering America, perhaps trying to obscure their origins and make tracking them more difficult. Some proudly kept their birth names.

The envelopes varied greatly in thickness. For Tobias von Altermann, the summary page contained only a few lines, and the folder had only three short news clippings—two in German, one in English (from a 1940s Idaho newspaper). For Nicholas Lorenz, the stack of pages barely fit in the envelope.

No facial resemblance in any of the men to my father. Papa and I must have inherited our looks from his mother. Three of them appeared to be related. So did another two pairs. I would later learn that the near look-alikes, though with different last names, were brothers. So, I might not only be seeing a grandfather among them, but a great uncle or two.

One of the thirteen—Ethan Cragg, the apparent boy wonder of the team—was obviously the youngest. Another, John Ledot, appeared the same age as most of the men, but his photos—two on his first page—were much older. One photo was very old. It was at least a second generation copy and very poor quality. I would guess the other to be early 20th Century, though I knew I had a lot to learn about dating photographs.

A perusal of Ledot’s vita on page one indicated that he headed the “zombie team,” and did his best to corral his independent-minded researchers as they pursued their different avenues of research (injections, gas inhalation, oral dosages, surgery, and what struck me as black magic).

From what I could guess of the team’s ages, any could have sired Papa. At the time of Papa’s birth, Cragg would have been in his teens, Ledot in his fifties, and the remaining 11 spread in between.

* * *

As I studied the photos, I kept looking at the binder that Papa wanted me to read first. “One at a time is good fishing,” he used to tell me (though, to the best of my knowledge, he had never fished in his life—it was, like so many of Papa’s one-liners, probably from an old movie).

I picked up the binder, but my eyes grew heavy, and I drifted into sleep. The time was early afternoon, but the sleepless night and the busy hours caught up with me. Like my father, I could nap mid-day with no problem.